Organizing a Petition Drive

Organizing a Petition Drive

Before a single signature is collected, those responsible for a petition drive should have the answers to the following questions:

-

- How many valid signatures are required (exact number)?

- How many total signatures are required (approximate number)? This number is based on historical validity rates for Libertarian petitions in your district. 70% is a typical validity rate, but it can vary widely (as low as 10% and as high as 90%). You also need to add a cushion to deal with things like petitions getting lost, a legal challenge, etc. So aim for a 10% cushion. Which means, if you need 1,000 valid signatures, and your validity rate is 70%, plan for 1,428 + 10% = about 1,570 raw signatures.

- What date does petitioning start?

- What date and time does petitioning end?

- What information is required to be on the petition and in what format?

- Who is responsible for printing the petitions?

- Who is permitted to circulate petitions?

- Who is permitted to sign petitions?

- Is there a distribution requirement (so many signatures per county or district)?

- Is there a requirement that signatures must be segregated by counties, town or other geographical divisions?

- Where should the signatures be submitted? Note that in Massachusetts, you must submit signatures twice: to cities and towns for certification, then collected and turned in to the state.

- Must the signatures be notarized?

- What other screwy requirements are there?

Now that you know the answers to these questions, you should map out the petition drive and divide the basic elements — time, money and signatures — into manageable units.

Assume a state with a requirement of 10,000 valid signatures, or approximately 15,000 total signatures. You have 120 days in which to collect the signatures. If you collect 125 signatures per day, you’ll meet the requirement (120 x 125 = 15,000). If 50 people collected 300 signatures apiece, or 2.5 signatures per day for 120 days, you’ll meet your requirement (2.5 x 120 x 50 = 15,000).

If 100 people collected — well, you get the idea. The point is: to quantify. Break everything — time, money, signatures — into manageable units, and get about getting the job done, unit by unit.

Get pledges from volunteers to collect a specific number of signatures. Ask each person to make a commitment for an actual number, whether it’s 10 or 1,000. Ask them to collect 5, 10, 20 or more signatures per day for every day of the petitioning period. Ask them anything. but get a firm commitment for a specific number.

Add up your numbers. For this example, assume they add up to 8,000 signatures. That’s not enough.

You’ll probably need to pay people to collect signatures to make up the volunteer shortfall, so you need to raise enough money to cover 7,000 signatures. The average rate is 50 cents per signature, so you need $3,500.

Go back to your LP members — especially the ones who refused to commit to a number of signatures -~ and ask then for specific dollar commitments. Explain that $100.00 is as good as 50 signatures, and ask them to “buy” 50 (or 100, 250, 500 and so on) signatures. If 35 people agree to contribute $100.00 each (or some other formula), you’ve raised your $3,500.00.

Once again: ALWAYS QUANTIFY. Don’t just say, “We need 15,000 signatures,” and leave it at that. Say, “If every one of our 300 members collects 150 signatures or contributes $100.00, we’ll achieve our goal of 15,000 signatures.”

The reason is this: If you give a person a reasonable, achievable goal and that person knows that other people like him are committing to the same goal, he’ll be motivated to achieve it, too.

Of course, some of your members will refuse to collect signatures or to send money. You’ll need to ask some of your reliable activists to “double up” on their pledges. Many of them will do it anyway, without being asked.

Mentorship is extremely important. Have your reliable activists go in teams with others who are not as comfortable or experienced as they are. This will build up your capacity and train future activists. Have experienced activists reach out to other mildly interested or prospect petitioners ahead of time. When out in the field, always gain commitment by setting another date by the end of the day. Offer to pick people up and car-pool. Then there is no excuses as to why they “couldn’t help that day”.

If, after you’ve asked everyone in sight for a pledge of signatures or money, your numbers still don’t add up to your goal, go ahead with the petition drive anyway. Many people will wait until you’re really desperate, and then they’ll respond. The real key is to get as much committed ahead of time as possible.

If you can account for 25% of your goal in pledges before the drive starts, you’ll probably make it.

Dealing with Paid Petitioners

Ideally, you’ll be able to find LP members who are willing to collect signatures for pay. If they are good petitioners, two or three of them can clean up a large percentage of your requirement over the length of the petitioning period. Try to get them to commit to a certain number of signatures per week, and check on them frequently.

If you can’t find LP members, or don’t have enough of them, you have no choice but to “go public” and advertise for petitioners. Occasionally, you’ll find people who have done it before for pay. Usually, the people who answer your ad will be novices whose primary interest is in making some quick money. A very high percentage of them will be either totally unreliable

or no good at petitioning, although surprisingly few will be downright dishonest. If twenty people answer your ads, figure five at the most to be worth a significant number of signatures. Emphasize that a good petitioner can make good money — $200 per day for 100 signatures, $400 per day for 200. Your best bet will be to contact LP National HQ and see if they can recommend paid petitioners who have a proven track record.

Treat your paid petitioners as you would treat valued employees. Make them feel wanted and needed. Be courteous and friendly, but not a pushover. Set specific, reasonable goals, and praise them for meeting them. Offer incentives if necessary.

Check on their progress on a regular basis. Throw a party for them occasionally, where they can meet other petitioners and exchange ideas and techniques. Suggest good places to petition. Pay them regularly and often, and set up definite paydays in advance for everybody, no exceptions.

Your classified ad can read: “Petitioners needed to collect signatures for political party. $100+ or more per day possible,” and include a name and phone number.

Screen the calls for people who are underage, non-citizens, or obviously inappropriate for the job. Many of the people who say they will come in for training won’t; keep your ad up as long as you can afford to. Try Craiglist.

During the Petition Drive

As Coordinator of the Petition Drive, you’ve taken on the responsibility for:

- Knowing and complying with all legal requirements;

- Establishing a “game plan” and sticking to it;

- Recruiting volunteer petitioners;

- Raising money;

- Supervising the paid petitioners.

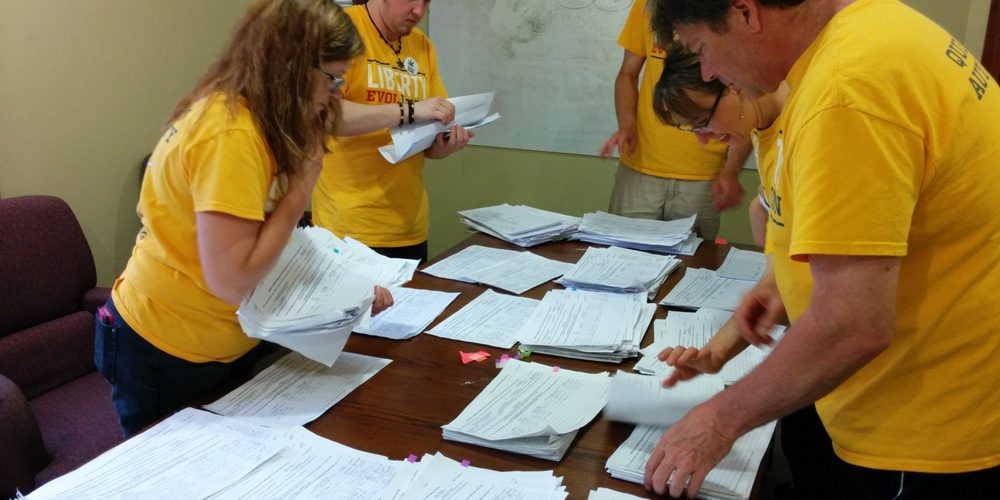

There’s one more thing, and it’s the most important: keeping track of the signatures. “Phantom” signatures are, unfortunately, the rule rather than the exception during petition drives. Phantom signatures are the ones you think you have, but don’t.

For example, you appoint three county coordinators, A, B, and C. They’re supposed to collect the completed petitions from the petitioners who are working in their respective counties.

When you call them up for a status report, A says he has 1,000 signatures. B reports 1,900 signatures, and C tells you he has 900. Great, you’ve got 3,000 signatures! Except that A was relying on the word of his “ace” petitioner who told him he had 250 signatures when he didn’t have any. B, on the other hand, could verify 1,000 of his signatures, but he was also counting the 900 that C gathered, since he didn’t understand that he was only supposed to report the signatures from his county, not C’s. Suddenly, you have 750 phantom signatures — one quarter of the total you thought you had.

The point is obvious: Don’t count any signatures unless you yourself have actually seen them. If geography makes this impossible, appoint one person in each location whom you can trust not to report signatures which he or she hasn’t actually seen.

There should never be more than two levels in the hierarchy; you, and a regional coordinator, if necessary. Don’t permit the regional coordinators to rely on the word of anyone else. And don’t accept signature counts based on anything other than what they have in hand at that moment.

Maintaining a policy of keeping a “conservative count” is absolutely crucial, even though it may call for you to be a son-of-a-bitch. Many ballot drives have failed precisely because sloppy signature counting showed more than there actually were. People tend to be optimistic; they want to believe other people, and they want the petition drive to succeed. So they tend to round up to the nearest thousand, or estimate the number of signatures they think are “out there,” and then report these numbers as hard facts.

In fact, there will be a “float,” that is, a certain number of signatures which actually do exist but which no one has ever seen. Since you don’t know how many there are, don’t count them. Let them be a pleasant surprise when they come in at the last moment.

The best way to ensure a “float,” and therefore a pleasant surprise, is to mail a petition to every LP member or sympathizer on your list, whether or not he has agreed to collect signatures, or even if you’ve never spoken to him. The signatures will start drifting in — one here, twenty there — when you need them most. But don’t count them until you see them.